Taste is often viewed as an innate quality—you either have it or you don’t. But is this really true? Can taste be developed and refined over time?

Today I’m exploring what taste means in a business context, how it affects customer relationships and business growth, and how, I argue, it can (read: should) be learned and cultivated, by anyone in your org.

You’re here because you recently subscribed or signed up for one of my resources—my course waitlist on Maven, lightning lesson, or Notion templates.

If someone sent you this post and you’re not subscribed, join those people learning how to tactically advocate for brand at your company. 📬

Of all the qualities brand leaders can have, taste is at once the most necessary and most nebulous. It’s one of those traits we feel we know when we see it—“she has impeccable taste” or “Aesop’s latest campaign was so tasteful.” But what are we really seeing? What’s informing our judgment of “good” vs. “bad” taste? Is taste a natural talent that, no matter how hard some of us try, we can never achieve?

Definitely not.

Taste isn’t born. It’s an intentionally developed skill that you can apply to your brand to build trust and drive conversion. This post explores what taste means in a business context, how it impacts customer relationships and business growth, and why it should be learned and cultivated by everyone in your org.

First, some context

Societally, “taste” refers to someone’s personal preferences and style: what they wear, what they’re into, their manners, how considered vs. spontaneous their approach is. It is subjective and personal—everyone’s taste is their own, and conceptions of good and bad are just as subjective. There are all kinds of tastes out there that don’t match your own, and that’s a good thing.

However, it’s fair to recognize that the concept of taste often carries a whiff of elitism and wealth, even in the face of the well-known phrase “money can’t buy taste.” Arbiters of taste (aka tastemakers) often sit in powerful places—Hollywood, politics, fashion, high-end restaurants, royalty or generational wealth. Yet in many cases, the taste such people are exhibiting and perpetuating is appropriated from diverse, grassroots youth culture.

I won’t go too deep into the sociological philosophy of this concept, but suffice to say it’s wise to be aware of this context when discussing the strategies and practices I lay out below—taste has baggage. (Here’s a great post that digs into that.)

What is taste at work?

In a business context, taste is more objective. Consider this definition as a starting point:

Taste in business is the ability to consistently make decisions that demonstrate respect for your audience, show deep empathy for their needs, and deliver aesthetically-pleasing experiences that drive positive business outcomes.

Clearly, this definition isn’t limited to brand work. Every professional, no matter the role, should make customer-centric decisions and deliver functional, delightful experiences—from a sales call to UI design and everywhere in between. And it’s no secret that such practices support growth.

But this is on brand after all, so let’s focus on what we know best.

Taste in brand results in a match between brand identity and user expectations that, in campaign and product touchpoints, feel considerate, relevant, and valuable to your target audience. Not surprisingly, this echos the principles of brand-market fit.

Having taste in a business context and applying it to your product and brand is a lot like being a beloved host—considering the needs and preferences of your guests (your audience), and adding a touch of your own personal flair (not enough to make it all about you) that makes your invitation the one no one ever turns down.

You (and your team) can learn great taste

Taste is a nuanced skill, the one I’m arguing isn’t innate but learned and cultivated. In practice, it’s an umbrella term for a number of skills you’re probably aware of and know how to practice (but are you practicing?! 😗). Let’s walk through a few:

Respect and empathy for your audience: Your product is probably a commodity, which means your audience has a choice. Respect that choice by valuing the customer’s time and intelligence, avoiding obviously manipulative tactics, and striving for genuine connection rather than transaction or conversion. Empathy goes hand in hand with respect—you develop it by understanding your target market’s needs, desires, and pain points. What motivations or fears are in the background? Tactically, this skill requires talking to customers and prospects, delving into ethnographic and psychographic data, and collaborating closely with front-line teams across your company to stay abreast of what they’re learning (but perhaps not proactively communicating).

Aesthetic sensibility: The skill most culturally associated with taste! 👀 Having an eye for design that’s not only visually appealing but also additive to the user experience and reinforcing to a consistent brand identity. This applies to everything from product screens to website design to email templates to social media posts to the emojis you choose to use (or how many). Some practices to developing this skill include competitor product teardowns, portfolio reviews, reading formal design content, and of course talking with the designers on your team (a lot).

Cultural fluency: Your awareness of current cultural trends, societal shifts, and contextual nuance. This allows teams to create experiences and messaging that feels timely and relevant—and to identify trends that actually align with your audience’s values. This skill involves knowing when to adopt trends and when to buck them in favor of something more authentic to your brand, and the ability to recognize when trends become overused or misused—you know when to hold and when to fold: Barbie was cute last summer, we’re on the brat train in ‘24. What’s next?

Ethical consideration: Good taste also involves ethical business and marketing practices that build long-term trust and respect with your audience. Ethics are a broad topic and probably the topic of a future post. For now, trust your gut. If you’re working at an unethical company, you probably know it, and maybe you’ve accepted it. That company will likely never have taste, and customers, consciously or subconsciously, will know it (looking at you, Wells Fargo).

When brand teams display these skills, they’re thinking holistically about the experience prospects and customers will have, which goes a long way towards earning the trust that’s so critical for retention and repeat purchasing. A good host makes it so that the guest wants to come back. A good brand manager (or a good marketer) thinks about what will lead to trust, loyalty, and retention.

Applying taste to branding

Let’s go a level deeper, from cultivating the skills that make up taste to displaying taste in your work. Remember, branding is everything about your business that a prospect or customer sees—consider these key qualities of tasteful branding:

Striking the right tone: This is your brand voice. It’s a skill to strike the right emotional chord with your audience, whether that’s professional and authoritative, friendly and casual, or somewhere in between. To get there, context is key. You might ask yourself:

Hey, fellow kids! Is now the right time for a meme, or will it make us seem out of touch?

Does this marketing approach align with current events and societal mood? What major global events might be on our prospects’ minds?

Are we matching the platform we’re using? A campaign that works brilliantly on TikTok might feel cringy on LinkedIn. Taste is about knowing the difference and adapting accordingly.

Attention to detail: A meticulous approach that ensures every element of your marketing—from the big picture strategy to the smallest design elements—requires a high bar of peer and management review. Attention to detail also demonstrates respect for your audience because it shows you’re paying attention to every aspect of their experience.

Consistency: The most critical aspect in building trust. This is the ability to maintain a consistent brand voice, look, and feel, throughout product expansions and evolutions. It’s very easy to slip when a visionary (opinionated) founder, executive or investor has a “great idea” for a new direction or a one-off reference to today’s zeitgeist moment. Is the disruption to your brand consistency worth the predicted bump?

Subtlety and restraint: Knowing when to make a bold statement and when to use a lighter touch. This includes understanding the power of white space, both in visual design and in messaging, and the ability to hold back from jumping on every cultural trend that comes along. Brands are built over the long term, but can become fixed in a prospect’s mind quickly. Do you want them to remember your one “different” touchpoint? Or to build a relationship with your core brand values and messages?

What brands have “good” taste?

Good taste goes hand-in-hand with achieving brand-market fit, and the brands who continually exhibit good taste are pretty evident. Like good hosts, they’ve thoughtfully considered their audience’s needs, and created an experience that meets those needs (and, ideally, aspirational desires.)

Whether people use the term “taste” or not, brand-market fit and good taste is why Apple is probably the most referenced company in terms of marketing and aesthetic decisions. Try this test: ask your founder or CEO what brands they admire most. If they don’t say Apple (or Nike, or Tesla, or Airbnb, or Patagonia…), color me pleasantly surprised!

Let’s not be boring—there are so many companies who have great taste from a business perspective. Gusto, Figma, Away, and Lemonade, while all very different, are all companies that have led with a clear sense of taste that’s unique to their category and industry.

These brands share a common thread: they deeply understand their audience and craft their marketing to appeal to their customers’ values and aspirations.

What is “bad” taste?

When we talk about things done “in bad taste,” it usually refers to dissonance between words and actions: what the brand or company has messaged that they stand for vs. what they put into the user’s hands and the experience their actions result in. This happens when either 1) something didn’t land with the audience as intended or 2) intentions were questionable or nonexistent.

Consider this definition:

Bad taste in business is characterized by decisions that prioritize short-term gains over user experience, disregard audience needs and preferences, or implement aesthetics that clash with functionality.

It manifests as manipulative tactics (eg. dark patterns in onboarding), inconsistent branding, or experiences that feel tone-deaf, outdated, or self-serving rather than user-centric. There are plenty of memorable, extreme examples—you know, the ones that have made headlines (Apple’s “Crush!” iPad ad, the meme-ified Peloton ad, that regrettable Pepsi ad with Kendall Jenner).

Advertising is most often where taste missteps show up, but they also show up in corporate management practices.

A few weeks ago, Intuit laid off 1,800 employees and labeled most of them as “underperformers.” Many people consider this handling to be done in poor taste, primarily because it shows a lack of empathy for the former employees. It was unnecessary to spurn employees further; there’s already a precedent for force-reduction layoffs. This decision is a reflection of their taste and it formed unintended brand perceptions: not that Intuit is a fast-moving, innovative AI-first company (what their messaging said), but rather that Intuit doesn’t have a great grip on its hiring or employee development practices (what their actions said). They come off as tone-deaf to overall economic concerns (valid or not) that many of their small business customers share.

A brand can exude taste overall, but still run campaigns, make statements, or behave internally in poor taste. This disconnect can damage brand perception and customer trust, and at worst can mean a loss of brand-market fit.

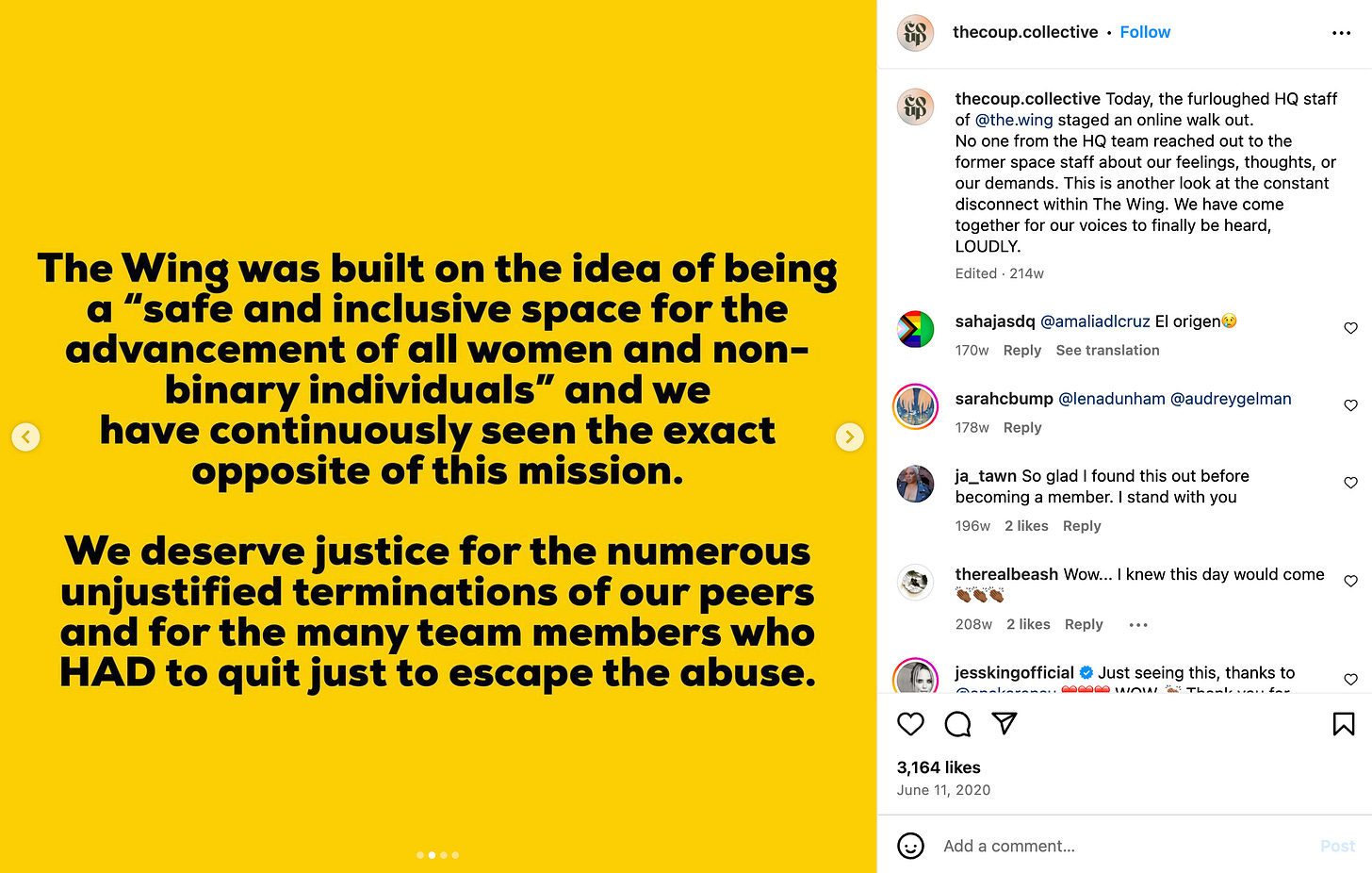

The Wing was a promising long-term player—a product with aesthetically great taste that generated immediate demand and brand-market fit. While they largely credit their shuttering to Covid-related financial challenges, they also made internal decisions that felt out of line with the experience they promised their customers, and they suffered extensive reputation damage as a result.

“But as the company’s narrative of economic success was on the rise, employees were starting to pierce its mystique, publicly revealing the schism between the company’s self-promotion and the realities of its working conditions.” (The New York Times)

Generally though, I think it’s more useful to talk about everyday examples where taste impacts growth outcomes. Most commonly, bad taste translates to poor customer experiences. It can manifest as:

Disregard for the customer’s time or needs (too many steps, too much information requested upfront, unclear instructions, an off tone of voice in customer support)

Messaging that doesn’t resonate with the target audience (or a tonal mismatch between the experience and the audience’s mindset)

Cluttered or confusing design that hinders rather than helps

Since growth marketing tends to prioritize short-term results, performant tactics can lead to decisions that might contribute to short-term adoption or new feature awareness, but end up creating a worse experience for the customer. In an upcoming post, I’ll talk about when those tradeoffs are worth it, but that’s where the tension stems from (subscribe to get that in your inbox).

How to develop your taste, right now

Getting tactical, here are a few specific tasks to add to your calendar this week to build up your taste skill:

Study UX design principles: Understanding how users interact with digital products and apps will better inform marketing decisions. The Laws of UX site was made for this. It also helps to look at good vs. bad examples!

Understand what “good” means in copywriting: Seriously such an undervalued skill—and it shows up in everything. Learn what clear, compelling copy looks like (from both a UX and creative perspective), and focus on how it speaks directly to your audience’s needs and desires.

The Go-To Guide for UX Writers and Content Strategists by Awen Wen

Why Your Links Should Never Say “Click Here” by Anthony Tseng

)

(16 Rules of Effective UX Writing by Nick Babich

Build empathy: Pair up with your research (and CS and account management) team to develop a deep understanding of your target audience. Take any opportunity you can to actually talk to customers, actively listen to learn not just about their immediate product needs but how they fit into bigger problems or goals they have.

Cultivate cultural curiosity: Stay informed on cultural trends and commentary, social issues, and technological advancements that affect your audience. Substack is ideal for this—some of my favorite publications on brand and culture specifically include

, , , , and . I’m also a forever-stan of ’s podcast Unseen Unknown and blog Concept Bureau.Analyze successful campaigns: Study marketing efforts that resonate with you and break down why they work (or fall short). A few of my favorite places to look: Brand New by Under Consideration, AdAge’s advertising section, @shwinnabegobrand on Instagram, Good Ads Matter on LinkedIn.

Taste isn’t static, it’s ever-evolving, and it helps to learn from other industries and include diverse perspectives in your decision-making.

It’s literally our jobs to have taste

PR and Comms, UX or brand copywriters, UX and UI and brand designers, and brand managers, to name a few—the goal of these roles is to create experiences that are consistent with the company’s values and messaging, and make it easy for the customer to move through product experience and conversion funnel.

There’s a lot to learn from each other—the strongest marketers know what goes into “good design,” know the jargon, and can speak the language with their partners. They’ve developed an understanding of UX and design principles and best practices, which should deeply inform marketing decisions around content development, distribution, and advertising to optimize for engagement and memorability.

Taste drives growth and loyalty

Good taste in marketing ultimately serves your audience and your business goals. While there’s a time and place for personal preferences, taste at work is about creating meaningful connections with your customers that drive long-term growth and loyalty, regardless of your personal taste. This is a hard lesson for founders and executives especially, because their personal taste is often the root of the product and brand. But here’s a nice metaphor for you—the beautiful blooming flower on a mature tree rarely looks like its root!

Taste, in a work context, isn’t an innate quality that some people have and others don’t, but a distinguishing skill that develops through intentional awareness and practice. Focusing on audience empathy and consideration, cultural awareness, and consistency across touchpoints, a marketer or leader of any discipline can refine their taste and create more effective, resonant messages that make your audiences want more. 🫚

My 4-week course on Maven, Brand for Growth-Stage Leaders, dives deep into how marketers can cultivate taste. The 5th cohort, starting September 2, just opened! You can use the code SUBSTACK to take $200 off your enrollment (until July 31), or join the waitlist for updates.

What are your go-to resources for learning UX (design and copy) best practices (ideally with examples)? Or favorite Substacks to read to cultivate cultural curiosity? I’d love to update this article with more links!

If you liked what you read, consider:

connecting with me on LinkedIn: Kira Klaas 👩🏼💻

commenting a question or topic you’d like to see next

sending to a friend 💌 or coworker 💬

I so often think of 'taste' in terms of creative or aesthetics, but I loved this breakdown of taste across all facets of the customer experience, and even employee experiences, workplace culture, and internal issues.

Enjoyed reading this perspective!